Testicular Cancer

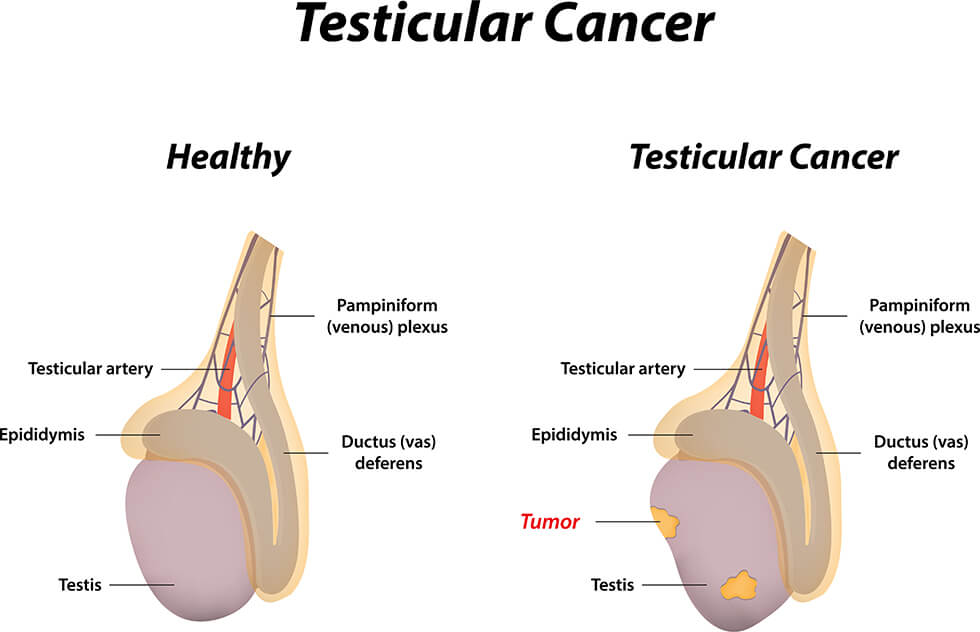

Testicular cancer affects the testicles—two important components of a man’s reproductive system. (The testicles are also called the testes.)

Found in the scrotum, these egg-shaped glands have two main jobs. One is to produce male sex hormones, including testosterone. These hormones give men masculine characteristics like facial hair and muscle mass. The testicles’ other job is to produce sperm cells, which may eventually fertilize egg cells.

The average age at diagnosis is 33.

Testicular cancer happens when cancer cells accumulate and form a tumor. It is relatively rare. The American Cancer society estimates that approximately 9,200 people assigned male at birth will be diagnosed with testicular cancer in 2023.

However, many of those people will be young. The average age at diagnosis is 33, and testicular cancer is the most common cancer among men aged 15 to 35.

Fortunately, many men with testicular cancer have a good prognosis. Testicular cancer is treatable, and it’s often curable. The American Cancer Society notes that a man’s lifetime risk of dying of testicular cancer is 1 in 5,000.

Read on to learn more about testicular cancer, its types, and its treatment options.

What are the different types of testicular cancer?

About 90% of testicular cancers start in germ cells. In men, germ cells go on to produce sperm cells. (In women, germ cells produce egg cells.) “Germ” in this sense comes from the word germinate, meaning “develop.” It is not related to the germs that cause illness. Sperm cells germinate (develop) from germ cells.

There are two main types of germ cell tumors (GCTs):

Seminomas usually grow slowly. People are usually in their 40s or 50s when diagnosed with seminomas.

Non-seminomas grow more quickly and tend to affect people in their teens, 20s, and 30s.

There are four types of non-seminomas:

- Embryonal carcinomas are aggressive and spread quickly.

- Yolk sac carcinomas are most common in children.

- Choriocarcinomas are rare, but aggressive.

- Teratomas are tumors that may contain tissue types not usually found in the testes, such as hair or bone. They are the result of errors in cell differentiation.

Stomal tumors form in tissue that is not made from germ cells. They account for less than 5% of testicular cancers. Leydig cell tumors form in the cells that produce testosterone. Sertoli cell tumors form in cells that provide nutrients to sperm cells, but they are usually not cancerous.

It’s possible for people to have different types of tumors at the same time.

Cause and risk factors of testicular cancer

Scientists do not know exactly what causes testicular cancer. But they have identified some risk factors.

Age

Testicular cancer is more common in men aged 15 to 35.

Family history

Having a parent or sibling with a history of testicular cancer increases a person’s risk.

Race and ethnicity

In the United States, testicular cancer is more common in non-Hispanic whites.

Past history of testicular cancer

A person who has had cancer in one testicle is at higher risk for developing cancer in the other testicle.

Germ cell neoplasia in situ (GCNIS)

GCNIS refers to abnormal cells that form in the testicle. They are not cancerous themselves, but they can lead to cancer.

Past history of undescended testicles (cryptorchidism)

People who had undescended testicles as children are more likely to have testicular cancer later.

Klinefelter syndrome

Men with this genetic condition are born with an extra X chromosome. They typically have small testicles, which may have been undescended at birth.

What are the symptoms of testicular cancer?

People who have testicular cancer may have the following symptoms:

- A lump on one or both testicles

- Swelling in the scrotum

- Pain or discomfort in the lower abdomen, scrotum, or testicle

- A shrinking testicle (testicular atrophy)

- Tenderness in the breast area

Men who have these symptoms should see their doctor as soon as possible. These symptoms do not always mean a man has cancer. However, catching cancer early usually leads to a better prognosis.

How is testicular cancer diagnosed?

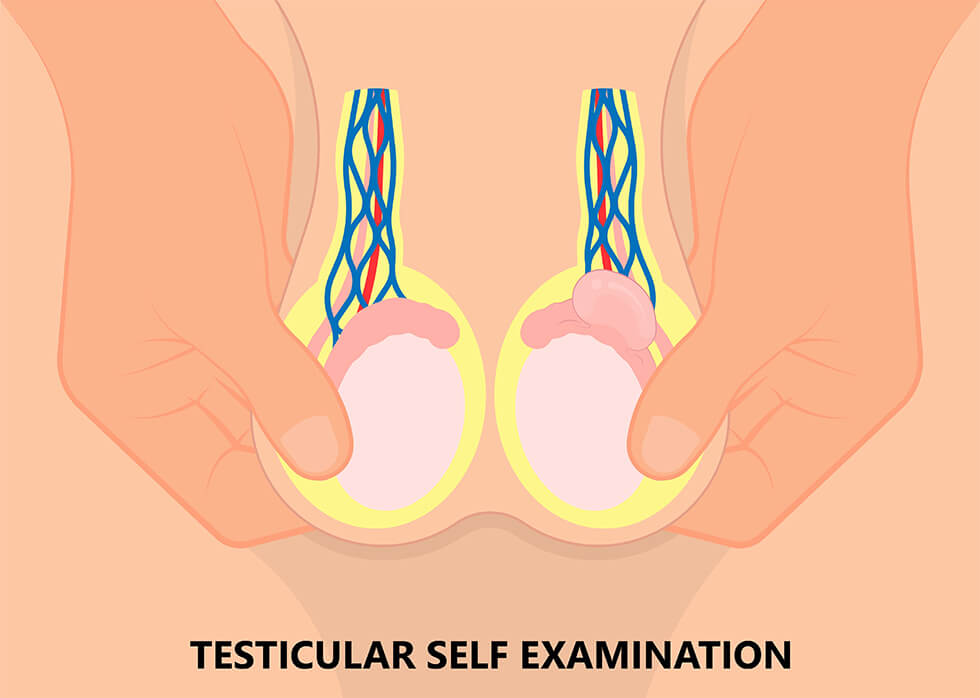

During physical exams, doctors routinely check a person’s testicles for lumps and swelling. People can also do self-exams at home.

If cancer is suspected, the following tests might be ordered:

Imaging tests

These tests may include ultrasounds, MRI scans, CT scans, or X-rays. They let doctors view the inside of the body to see tumor locations and determine whether any cancer cells have spread.

Blood tests

With blood tests, doctors can check for tumor markers. These are substances that, if present in the blood, suggest that a certain type of cancer is present. Some examples of tumor markers are alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG or beta-HCG), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH).

Biopsy

If imaging tests show cancer, the affected testicle may be removed during a surgical procedure called an orchiectomy. After the testicle is removed, a specialist examines it for cancer cells.

Stages of testicular cancer

During diagnosis, doctors determine the stage of testicular cancer. Staging provides information on where cancer cells are located and whether they have spread to other areas in the body.

Stage 0

Stage 0 refers to germ cell neoplasia in situ (GCNIS). Abnormal cells are present, and while they aren’t cancerous, they could become cancerous in the future.

Stage I

Cancer cells are found in a testicle, but not in lymph nodes or other parts of the body.

Stage II

Cancer cells have spread from a testicle to one or more nearby lymph nodes. But cancer is not found in other parts of the body.

Stage III

Cancer is found beyond the nearby lymph nodes. It might have spread to other parts of the body.

How is testicular cancer treated?

Doctors base cancer treatment decisions on a patient’s overall health, the stage of their cancer, and the type of tumors found.

Radical inguinal orchiectomy

During this surgical procedure, the affected testicle is removed through an incision in the groin. The spermatic cord is also removed. The spermatic cord includes nerves, blood vessels, lymph vessels, and part of the vas deferens, the pathway sperm cells take during ejaculation.

Some men feel self-conscious about their genital appearance after the removal of one or both testicles. They may choose to have a testicular prosthesis (an artificial testicle) implanted to maintain the appearance of two testicles. The size of the prosthesis is matched with the size of the original testicle(s).

Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND)

This procedure removes the lymph nodes that sit behind the abdominal organs. It might be done at the same time as an orchiectomy or as a separate surgery later. Not all men have this surgery, however.

This surgery may be open, with a large incision made in the abdomen. Or, it may be laparoscopic, with smaller incisions in the abdomen. In a laparoscopic procedure, the surgeon manipulates long, thin surgical tools through the incisions. But the surgeon’s hands remain outside the body.

Other surgeries

Cancer cells may be surgically removed if they have spread to other parts of the body, such as the lungs or liver.

Radiation

This approach destroys cancer cells with high energy X-rays. These rays are delivered through an external device (outside of the body). Men may have radiation if cancer has spread to their lymph nodes. Radiation may also be given after surgery to reduce the risk of the cancer coming back.

Chemotherapy

Men whose cancer has spread beyond the testicle may undergo chemotherapy. This treatment uses powerful drugs, which may be taken in pill form or given through an IV. The drugs move through the bloodstream, killing cancer cells that have spread around the body. Chemotherapy may also be used after surgery, to reduce the risk of a cancer recurrence.

Surveillance

People in Stage 0 or Stage 1 of testicular cancer might undergo surveillance. With this approach, treatment doesn’t start right away. Instead, doctors carefully monitor the patient’s health with frequent checkups and testing to see how the cancer is progressing. Treatment begins when necessary.

Patients may also have surveillance after surgery to make sure the cancer does not recur. If it does, treatment begins again.

Considerations to make before treatment

Testicular cancer often affects younger men who may want to have children in the future. However, cancer treatment can affect fertility and hormone production.

Fertility issues

If a man has both testicles surgically removed, his body will no longer be able to produce sperm or testosterone. As a result, he will become infertile. (Note: If only one testicle is removed, the remaining testicle should be able to make adequate amounts of sperm cells and testosterone.)

Radiation and chemotherapy can also affect the production of sperm and testosterone.

In addition, nerves that control ejaculation can be damaged during RPLND. This can lead to retrograde ejaculation, where semen travels backward into the bladder instead of forward out of the penis. Retrograde ejaculation doesn’t harm the body, but it makes it difficult for men to conceive children.

Men who wish to father children may opt to bank their sperm before starting testicular cancer treatment. In this way, sperm cells are frozen and stored for use later.

Testosterone deficiency

Testosterone deficiency after cancer treatment is also a possibility. If a man’s body no longer makes enough testosterone, he may experience symptoms like fatigue, moodiness, muscle weakness, reduced sex drive, and erectile dysfunction (ED).

These symptoms may be managed with testosterone replacement therapy.

Can testicular cancer be prevented?

Testicular cancer cannot be prevented. But when caught early, it may be easier to treat. Urologists recommend that men do monthly self-exams to check their testicles for lumps, changes in size, swelling, or any other unusual symptoms. A man’s doctor can give him complete self-exam instructions.

Resources

American Cancer Society

“Chemotherapy for Testicular Cancer”

(Last Revised: May 17, 2018)

https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/testicular-cancer/treating/chemotherapy.html

“Fertility and Hormone Concerns in Boys and Men With Testicular Cancer”

(Last revised: May 17, 2018)

https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/testicular-cancer/after-treatment/fertility.html

“Key Statistics for Testicular Cancer”

(Last revised: January 12, 2023)

https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/testicular-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

“Radiation Therapy for Testicular Cancer”

(Last Revised: May 17, 2018)

https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/testicular-cancer/treating/radiation-therapy.html

“Surgery for Testicular Cancer”

(Last revised: May 17, 2018)

https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/testicular-cancer/treating/surgery.html

American Urological Association

Stephenson, Andrew, MD, et al.“Diagnosis and Treatment of Early Stage Testicular Cancer: AUA Guideline (2019)”

(2019)

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/testicular-cancer-guideline

Cleveland Clinic

“Germ Cell Tumor”

(Last reviewed: July 15, 2022)

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/23505-germ-cell-tumor

“Teratoma”

(Last reviewed: November 16, 2021)

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22074-teratoma

“Testicles”

(Last reviewed: August 9, 2022)

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/23964-testicles

“Testicular Cancer”

(Last reviewed: May 2, 2022)

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/12183-testicular-cancer

Johns Hopkins Medicine

“Types of Testicular Cancer”

(November 18, 2019)

https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/testicular-cancer/types-of-testicular-cancer

MedlinePlus.gov

“Klinefelter syndrome”

(Last updated: April 1, 2019)

https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/klinefelter-syndrome/

Urology Care Foundation

“What is Testicular Cancer?”

(Updated: January 2023)

https://www.urologyhealth.org/urology-a-z/t/testicular-cancer